Command Performance: Using the Incident Command System (ICS)

Sometimes there is a good reason to reinvent the wheel—for example, if you are in business and the current “wheel” is a proprietary product controlled by your competitor.

However, sometimes the tried-and-true solution is the best way to go, and we believe that is the case when it comes to emergency management systems.

What is an emergency management system?

An emergency management system is the methodology an organization uses for managing emergencies.

Having such a system is critical for the protection of your organization since if and when you do face an emergency, your problems can be made significantly worse if your response is hampered by role confusion and poor communication.

So you should definitely have an emergency management system in place—but what kind of system?

This is where not reinventing the wheel comes in because in our opinion the best way to organize your crisis management team and response is to follow the method known as the Incident Command System or ICS.

The Incident Command System (ICS) Methodology

The ICS is a widely used method for organizing emergency response teams, particularly in the public sector. It is: :

- Freely available for use by any organization.

- Time-tested (it originated in the late 1960s).

- Endorsed by the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA).

- Of such proven effectiveness it has been adopted for use by governments and organizations all around the world.

In our opinion, you definitely need an emergency management system and ICS is a good framework and methodology.

For these reasons, today’s post will be devoted to providing an overview of ICS.

We’ll start with a brief description of ICS then provide a table setting forth how an emergency response team is organized under the ICS system. We’ll conclude with a few tips and observations about how to make ICS work for you.

Overview of ICS

ICS was first developed in the late 1960s and 1970s by agencies in Arizona and Southern California that were engaged in fighting wildfires. It has since been adopted or recommended for use by FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security, numerous state and local agencies, many private companies, and emergency management agencies in countries ranging from Canada to New Zealand.

ICS consists of a standard management hierarchy and procedures for managing temporary incidents of any size, scope, or complexity. It provides an organizational structure for incident management and a guide for planning, building, and adapting that structure.

Establishing ICS early in an incident shifts the response from reactive execution toward proactive thinking. Moreover, when multiple agencies or businesses involved in responding to an event use ICS, the fact that their crisis teams share a similar structure and common language means they can collaborate better, improving their response.

ICS Structure and Responsibilities

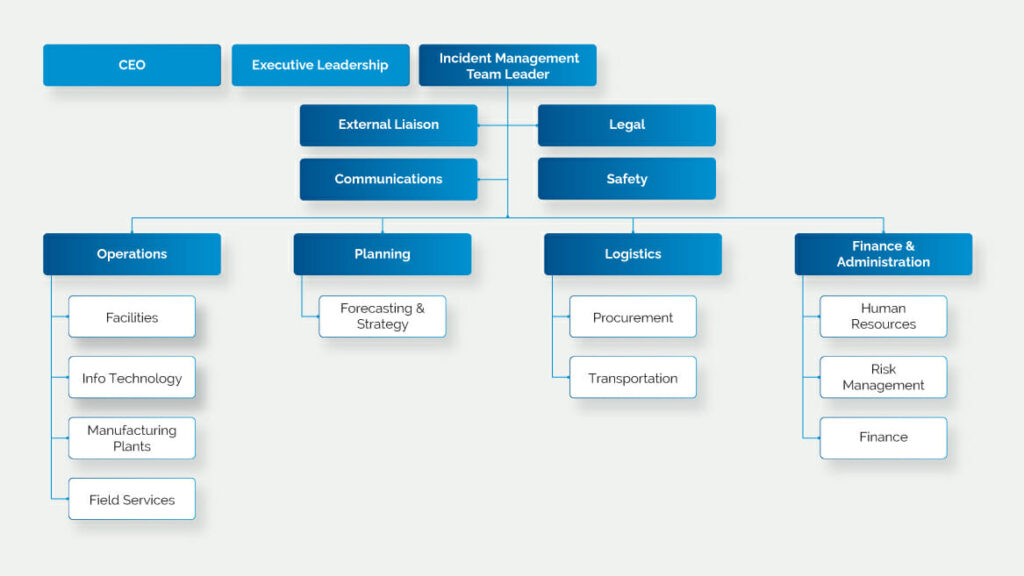

The ICS structure is built around five major management activities or functional areas:

- Command. Includes Incident Commander, Safety, Liaison, and Communication. Sets priorities and objectives and is responsible for overall control of the incident.

- Operations. Accountable for all tactical operations necessary to carry out the plan.

- Planning. Responsible for the collection, evaluation, and distribution of information regarding incident development and the availability of resources.

- Logistics. Responsible for providing the necessary facilities, services, and materials to meet incident needs.

- Finance/Administration. Responsible for monitoring and documenting all costs while providing the necessary financial support related to the incident.

The table below (adapted from Ready.gov) shows the specific responsibilities for each ICS role:

| Role | Responsibility |

|---|---|

| Command | Incident Commander

Safety

Liaison/Communication

|

| Operations |

|

| Planning |

|

| Logistics |

|

| Finance/ Admin |

|

Tips for Making the Most of ICS

Here are a few tips and observations to help your organization make the most of ICS:

- Think of ICS as a framework rather than as a hard-and-fast methodology. ICS is flexible enough to be scaled up or down depending on the size of your organization and the seriousness of the incident.

- Think in terms of concepts, roles, and needs. In a small incident, one individual might perform multiple roles. In medium-sized incidents, there might be a one-to-one correspondence between individuals and roles. Finally, in large incidents, you might require the whole team to carry out a role.

- Not every functional area will be needed for every incident. All incidents will have a Command function and almost all will have an Operations function. The remaining activities tend to be used only in larger or longer incidents.

- During the incident, each person has one boss! The strict tree structure of ICS means everybody knows who they work for and every supervisor knows who works for them. This greatly facilitates communication and coordination during the emergency.

- Critically, roles and responsibilities are not based on the management structure or title in the organization. Successfully managing incidents requires the individuals involved to put their egos to one side for the duration. Roles should be filled based on skillset and temperament rather than seniority. There might be times during the incident when the more senior person reports to a person lower in the management structure. This can be challenging but experience shows it is for the best and can usually be managed.

- When senior management arrives to monitor the scene or get an update, they should not automatically take over. It is often the case that the person already in charge on the scene is the best qualified to remain in command.

- Any transfer of command responsibility from one person to another should be explicit and accompanied by a briefing, if necessary. Others at the incident should be notified of the transfer. When and if a change in command does occur, planning should note the change in its organization chart.

- It is important to have clear communications throughout the incident. Communicating clearly and completely, in everyday language, reduces the potential for confusion, reduces the time spent clarifying message content, and allows individuals at a greater distance from the situation to monitor and comprehend what is happening. All of these things will speed up the process of remedying the incident.

Conclusion

To sum up: Your organization definitely needs an emergency management system, and in this case, there’s absolutely no need to reinvent the wheel: Look into ICS and adopt it for your organization. Once you do, your emergency response program will be off and rolling.For more information on ICS, check out the page Incident Management on the government website Ready.gov. It contains in-depth discussions of ICS and the National Incident Management System (NIMS) of which it is a part.